Having defined our approach to value investing and explained what we do in last quarter’s investor letter, we now feel compelled to discuss what we don’t do. This is largely because of a straw man being constructed (mainly, it seems, by people who are not value investors themselves) about what value investing represents in order to explain why it has not fared as well as ‘quality’ or ‘growth’ investing in the last few years. The narrative is that value investors own poor businesses which may have the odd bounce, but which are doomed to decline in the long run whilst growth investors do the opposite. This is also used to predict that growth stocks will continue to perform well (despite their record high valuations) and value stocks will continue to do badly (despite record low valuations). Needless to say, we do not subscribe to this theory as discussed below.

Misleading titles

When it comes to investing, the labels ‘growth’, ‘quality’ and ‘value’ strike us as somewhat arbitrary, a point also made by legendary investor Warren Buffett.

“We think the term value investing is redundant. What is investing if it is not the act of seeking value at least sufficient to justify the amount paid? Consciously paying more for a stock than its calculated value in the hope that it can soon be sold for a still higher price should be labelled speculation”

Warren Buffett, 1997 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting

We would completely agree with this. Despite being labelled value investors, we will naturally look at the quality of a firm (in terms of things like its market position, return on capital, balance sheet strength and cash generation) when we are researching a stock for potential inclusion into the portfolio. All else being equal, we would prefer to buy a high-quality business than a low-quality business. Similarly, the calculation of the intrinsic value of a business will involve an estimation of its likely future growth rate and again, we would prefer to own a high growth stock than a low growth one. One needs to acknowledge, however, that there is a price which is too high for even a good quality, high growth business.

In our previous letter, we used Microsoft as a great example of a high-quality fast-growing business, but we noted that if you purchased the shares in 2000, it would have taken you sixteen years to get back to break even. This was not due to any issue with the underlying business, but merely because you would have overpaid for it at the outset. What we did not mention previously, however, was that we purchased shares in Microsoft in 2010 when it was trading on a single digit price-earnings ratio. At that point in time, Microsoft was a quality business whose shares represented good value the two are not mutually exclusive. Hopefully this illustrates that, as value investors, we do not spend our time looking for businesses which are lowly valued but in secular decline. If high quality businesses are available at an appropriate price, we are delighted to own them. What we won t do, however, is overpay simply because a business is deemed to represent quality or based on a macroeconomic forecast of an environment in which quality should do well.

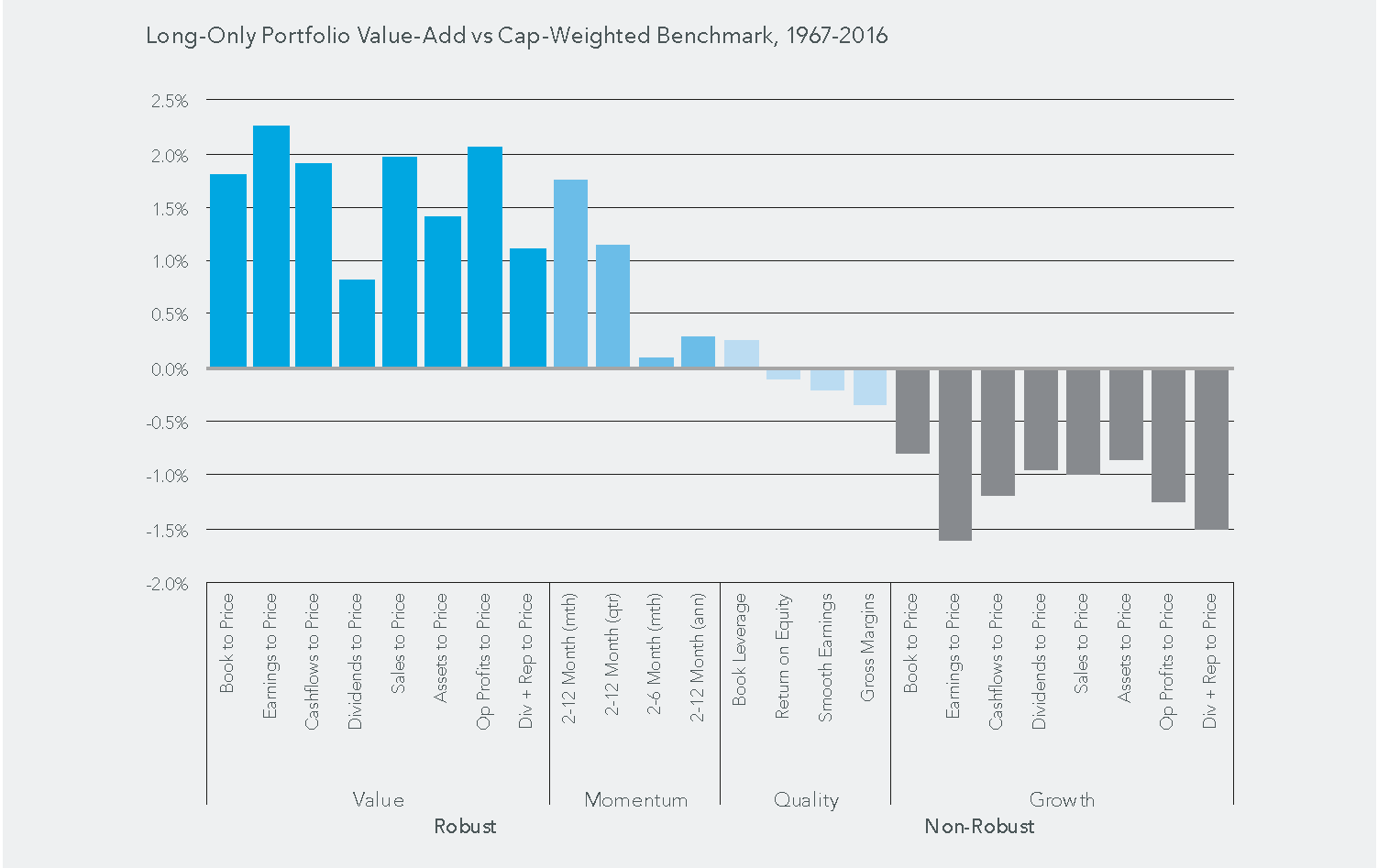

There is no evidence that buying quality irrespective of value works

As investors, we want to employ a strategy which has been proven to exceed the return of the benchmark index over time. Whilst we can find plenty of empirical evidence to suggest that value investing delivers this in the long run, we have yet to see any evidence that buying growth or quality regardless of value works. The chart on the following page demonstrates this well and it should not come as a surprise. Value investors can earn a premium because they are prepared to own businesses that other investors don t like, and which are considered riskier than the average stock. To believe that quality or growth investing works you would have to be convinced that investors earn a premium by owning companies that are popular with others and whose operating performance is more consistent. More than this, you would have to believe that the market is so inefficient that this premium would not be competed away. This strikes us as completely counter intuitive.

Value factors have added long-term value, whereas quality and growth have not

Source: Research Affiliates to December 2016

From today s starting point, however, it seems even more unlikely that buying growth or quality will be a successful investment strategy. Because many investors are currently fearful about the economic cycle, they have sold cyclicals and bought quality stocks, thus opening up one of the largest gaps in valuation between the two groups ever. Anyone who believes that valuation is the best guide to future returns should be wary of owning such expensive stocks and yet expecting them to deliver strong future returns.

Do value investors just own businesses in secular decline?

As mentioned in the introduction, a narrative has emerged which postulates that, as the pace of technological change has accelerated, so traditional business models are being disrupted at an unprecedented rate. According to this thesis, value investors naively own lowly-valued businesses which are in secular decline (so called value traps) whilst growth investors own the disrupters who will be the survivors in this winner takes all world.

In this environment, valuation becomes meaningless, and you will frequently here tropes such as Amazon always looked expensive and that didn t stop it going up a hundred-fold . What is seductive about this theory is that we can all identify elements of truth in it. The demise of HMV, for example, or of various high street department stores, simultaneous to the seemingly unstoppable rise of Amazon, is something we are all familiar with. What is also useful about this theory is that it can be extrapolated into the future to justify why growth stocks will continue to outperform despite the substantial valuation gap between the two cohorts. But, as Mark Twain said, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble, it’s what you know that just ain’t so”, and hence we believe there are elements of this thesis which do not stand up to scrutiny.

If this notion of a business world that is polarised between disrupters and the disrupted reflects reality, you should expect to see an increased dispersion between the profitability of these two groups and yet this does not appear to have happened. Despite the high-profile examples of a new entrant disrupting an established business, the question is not whether this has happened in isolated examples but the extent to which it has happened in aggregate. Two notable studies from Cliff Asness1 and Rob Arnott2 have investigated this theory and found that, contrary to popular belief, there has been no degradation in returns on capital or earnings for value quintiles. In fact, value portions of the market have done slightly better. Asness’s analysis concludes that the primary driver of value s underperformance has simply been value getting cheaper and growth getting more expensive, as has been the case in every past cycle where value has underperformed (of which there have been many). It should be obvious that this is not a sustainable source of returns as it seems unlikely, based on historical data, that growth stocks can re-rate forever and value stocks can de-rate forever. At some point, this dispersion moves in the other direction and value stocks recommence their outperformance.

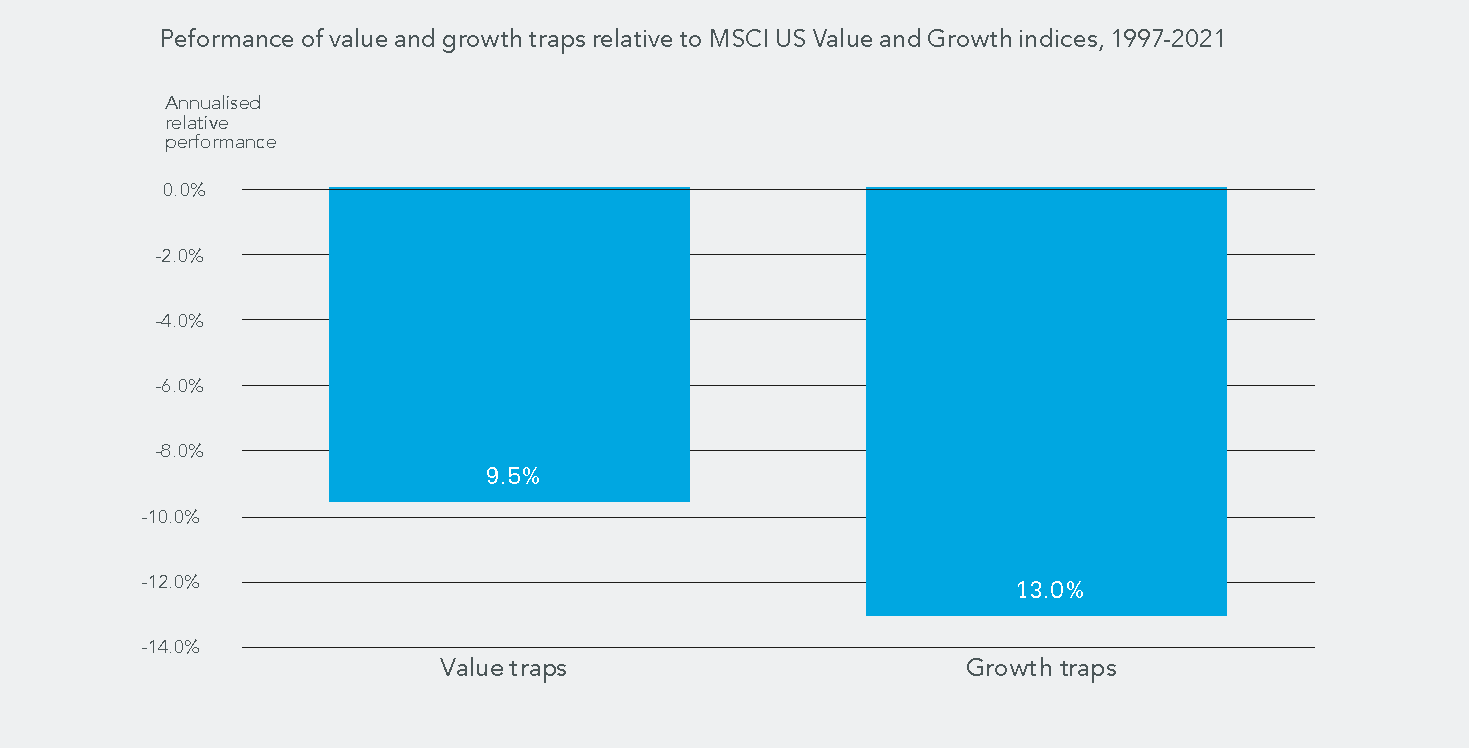

Disruption is as old as capitalism and hence it is something that all investors have to cope with. There is no obvious reason why value investors would be more exposed to the forces of creative destruction than any other type of investor. In fact, a recent piece of research from GMO3 suggests that growth investors are more exposed to disruptive influences, that there are more growth traps than value traps and that they tend to fall further when they disappoint. This makes sense since new entrants aiming to disrupt an industry are more likely to be attracted to profitable high growth areas than more mature businesses. Furthermore, growth stocks tend to have high expectations embedded into their share prices and hence, when they disappoint, they tend to fall further than value stocks which have much lower expectations.

Growth traps underperform value traps

Source: GMO to 30 June 2021

Misdiagnosed structural decliners offer opportunities for value investors

Knowing in advance which businesses are suffering a temporary setback, and which are in long-term decline is not as easy as many would seem to believe. Returning to our Microsoft example, the shares became cheap because many investors had convinced themselves, wrongly as it turned out, that it was going to be disrupted by firms such as Apple and Google. This demonstrates how investors can frequently under-estimate the ability of businesses to adapt and change. Hence, lowly valued shares which investors have written off as secular decliners, often turn out to be more resilient than expected and hence produce strong returns as views change and they ultimately re-rate.

Are energy stocks in secular decline?

This leads neatly on to a discussion of the energy sector, which is a great example of an industry that has been written off by many investors that believe it is in secular decline as the world transitions to a carbon neutral future. Fund managers taking this view have sold their holdings of energy companies, whilst others have excluded them from their funds for ESG reasons. We are obviously very mindful of the ESG issues surrounding the sector but our approach to sustainable value investing favours engagement over divestment. This is something we intend to write more about in a future issue of this quarterly newsletter but, in the meantime, the actions of other market participants do appear to have contributed to an attractive long-term opportunity, with valuations driven down to their lowest level in years. To give some idea of how dramatic this decline has been, in 2000 the energy sector accounted for 30% of the S&P 500 Index. In 2009 this figure was 15% and today it is 3%. To put that in context, the Technology sector is now 28% of the S&P 500 and both Apple and Microsoft individually represent more than 5% of that index.

The irony of the energy sector being out of favour is that it comes at a time when the fundamentals are looking very promising. In response to falling energy prices as well as environmental pressure, energy companies have slashed their capital expenditure, with the 43 largest listed oil & gas producers having reduced aggregate exploration & production spending by around a half (source: JP Morgan). Some believe that as Covid subsides and world economies re-open, there may be insufficient production to meet rising energy demand and, as we write, this thesis seems to be playing out with Brent crude oil at $83 per barrel, up 120% over the last year, and natural gas at 300p per therm which is up 700% in the last twelve months.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice. No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment.

Needless to say, this rise in prices is having a positive impact on the profitability of the energy companies. If we use BP as an example, management has guided that at an oil price of $70 per barrel, the company will produce free cash flow per share of $0.73 which, at the current dollar share price of $4.50, equates to a 16% free cash flow yield (note, this is after all the capex required to transition the business to renewables production). At $60 per barrel, the company expects to be able to deliver share buybacks of around $1bn per quarter and have capacity to increase its dividend by around 4% each year through to 2025 (source: BP). These plans imply that approximately 10% of its current market cap (split broadly equally between a c. 5% dividend yield and an annual cut of c. 5% to its share count) can be returned to shareholders each year. In other words, investors can expect BP to return more than 55% of its current market cap to its shareholders by 2025.

Conclusion

Across the fund management industry, investors seem to have drifted away from value investing, a discipline that has worked in the long run but not recently, towards a style now labelled quality or growth investing, which has worked recently but not in the long run. This style drift is often justified by claims that the investing world is now polarised between the winners and losers and yet, as we have seen, the data does not seem to support this thesis.

We continue to believe that valuation provides the best guide to future returns and given some of the low valuations available today, we believe investors will be handsomely rewarded by sticking with value investing.

Yours sincerely

Ian Lance, Nick Purves

1 ‘Is (systematic) value investing dead?’, by Cliff Asness, AQR, May 2020

2 ‘Reports of value’s death may be greatly exaggerated’, by Rob Arnott, Campbell Harvey, Vitali Kalesnik, Research Affiliates, January 2021

3 ‘Dispelling myths in the value vs. growth debate’, by Ben Inker, GMO, September 2021

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so.

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Nothing in this document should be construed as advice and is therefore not a recommendation to buy or sell shares. Information contained in this document should not be viewed as indicative of future results. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

This document is issued by RWC Asset Management LLP ( RWC ), in its capacity as the appointed portfolio manager to the Temple Bar Investment Trust Plc. RWC, is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

RWC may act as investment manager or adviser, or otherwise provide services, to more than one product pursuing a similar investment strategy or focus to the product detailed in this document. RWC seeks to minimise any conflicts of interest, and endeavours to act at all times in accordance with its legal and regulatory obligations as well as its own policies and codes of conduct.

This document is directed only at professional, institutional, wholesale or qualified investors. The services provided by RWC are available only to such persons. It is not intended for distribution to and should not be relied on by any person who would qualify as a retail or individual investor in any jurisdiction or for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.

The information contained herein does not constitute: (i) a binding legal agreement; (ii) legal, regulatory, tax, accounting or other advice; (iii) an offer, recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell shares in any fund, security, commodity, financial instrument or derivative linked to, or otherwise included in a portfolio managed or advised by RWC; or (iv) an offer to enter into any other transaction whatsoever (each a Transaction ). No representations and/or warranties are made that the information contained herein is either up to date and/or accurate and is not intended to be used or relied upon by any counterparty, investor or any other third party. RWC bears no responsibility for your investment research and/or investment decisions and you should consult your own lawyer, accountant, tax adviser or other professional adviser before entering into any Transaction.

How to Invest

The Company’s shares are traded openly on the London Stock Exchange and can be purchased through a stock broker or other financial intermediary.