By Ian Lance, co-portfolio manager

Every time I visit my mother, she asks me why the stock market is doing so well when the current government appears determined to hamper the economy by raising taxes, increasing the cost of employing staff, driving up energy prices or just generally getting in the way of business by adding layers of bureaucracy and regulation.

I suspect she is not alone in wondering this. Many Temple Bar shareholders may feel the same unease, with political and economic headlines remaining relentlessly gloomy. The purpose of this letter, therefore, is to explain why such headlines can often be a poor guide to long-term investment outcomes – and explore why periods of widespread pessimism can, in fact, create opportunity rather than destroy it.

Macroeconomic forecasting is not a reliable investment strategy

Very few investors can predict with confidence when recessions will occur, how severe they will become or how long they will last. The same is true of monetary policy. Accurately forecasting changes in central bank behaviour, and then successfully judging how markets will respond to them, is extraordinarily difficult.

If perfect foresight were reliably achievable, macroeconomic forecasting would be a powerful investment tool. In practice, this is rarely possible. Warren Buffett famously advised against it as an investment strategy and advocated exploiting the over-reaction of others to the swings of the economic cycle.

“We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen. Thirty years ago, no one could have foreseen the huge expansion of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8% and 17.4%. But surprise: None of these blockbuster events made even the slightest dent in Ben Graham’s investment principles. Nor did they render unsound the negotiated purchases of fine businesses at sensible prices. Imagine the cost to us, if we had let a fear of unknowns cause us to defer or alter the deployment of capital. Indeed, we have usually made our best purchases when apprehensions about some macro events were at a peak. Fear is the foe of the faddist, but the friend of the fundamentalist.”

Source: Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders, March 1995

Economic events impact share prices more than fundamentals

We believe that our ability to add value as investors comes from focusing on where a company’s profits are likely to be over the long term (five or more years), rather than the short-term earnings momentum that most other investors prioritise (often just the next quarter). When we buy equity in a business, we are buying a share of a very long-term stream of future cashflows. From that perspective, a temporary reduction in profits over a year or two does very little to alter the long-run intrinsic value of that business.

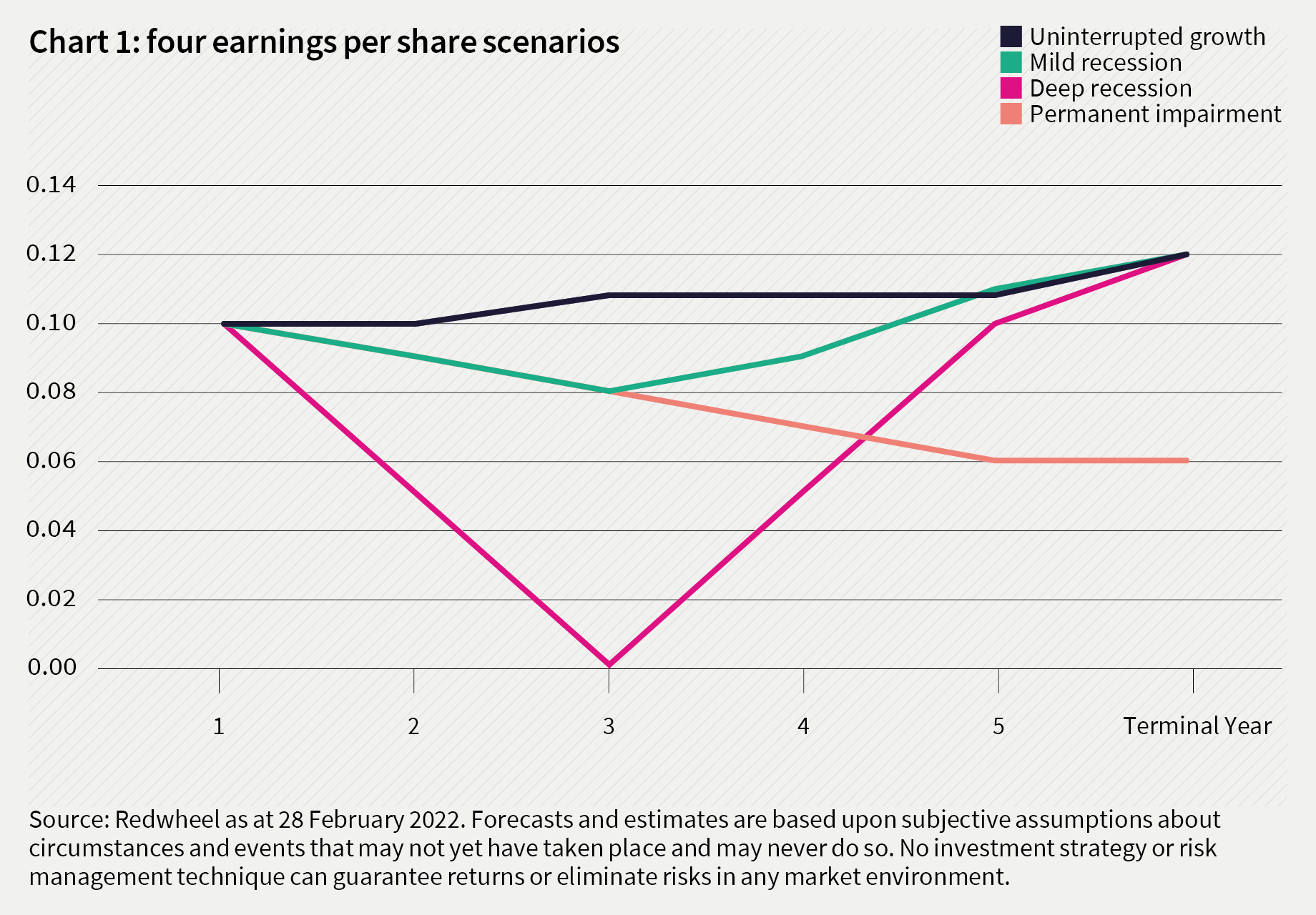

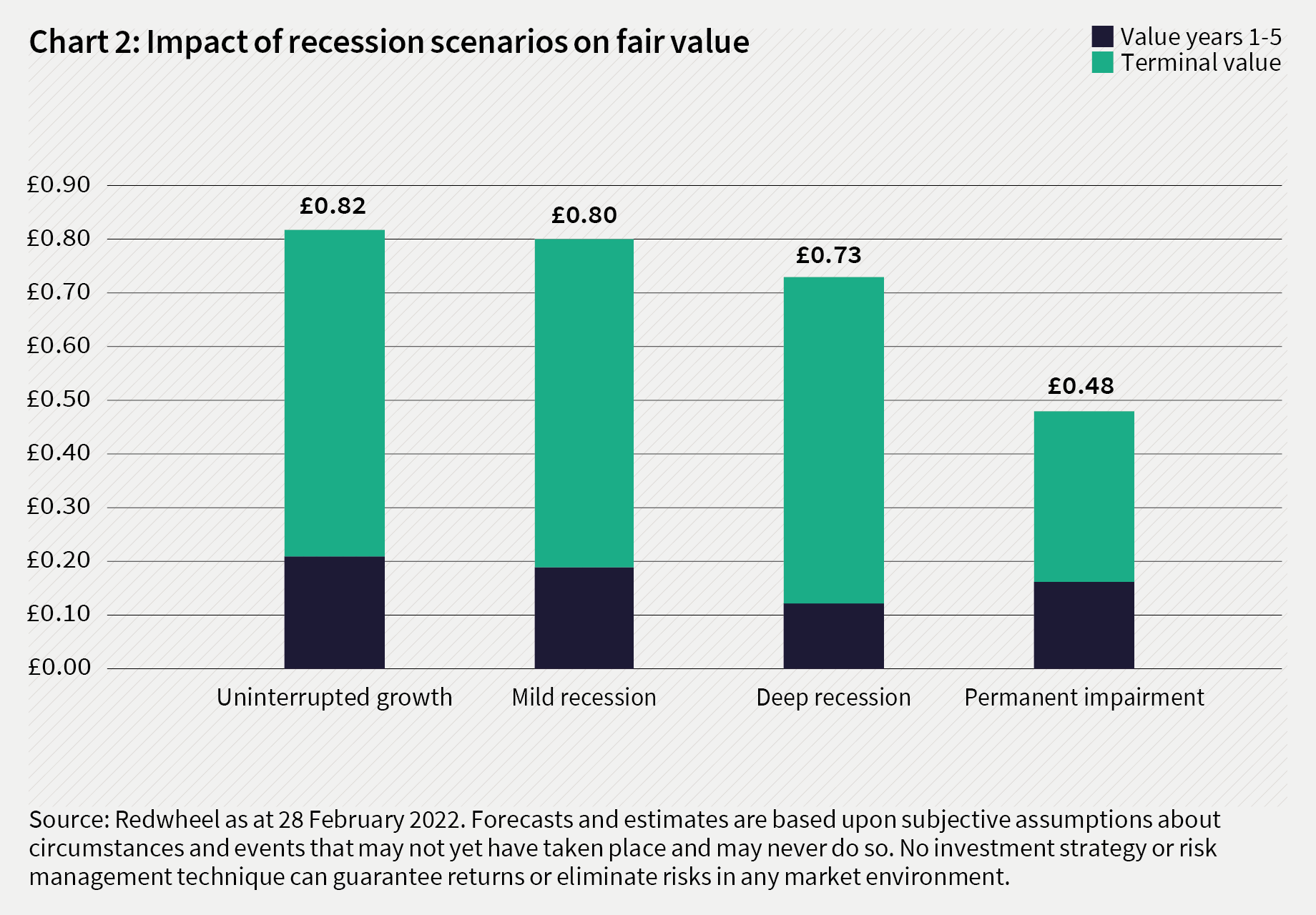

As we explored in our January 2022 newsletter, this can be illustrated using a simple net present value (NPV) analysis, which shows how different earnings outcomes affect a company’s intrinsic value. As shown in charts one and two below, the key point is that temporary earnings declines typically have a surprisingly modest impact on long-term value, provided the underlying earnings power of the business remains intact.

Even in a severe recession scenario, where profits are sharply reduced for a period, the impact on intrinsic value is limited. It is only when earnings suffer permanent impairment, and fail to recover to prior levels, that long-term value is significantly affected.

Despite this, many investors have a tendency towards extrapolation and over-reaction to short-term news flow and earnings trends. In doing so, they can create the very mis-pricings that longer-term investors like us are seeking to identify and capture.

The difference between investment and speculation

In essence, this distinction explains the difference between investment and speculation. An investor recognises that buying equity means owning a share of a long stream of future cashflows and seeks to take advantage of situations where share prices fall well below a conservative estimate of intrinsic value. From this perspective, a period of weaker earnings does not normally alter the long-term value of a business materially.

A speculator, by contrast, is trying to guess where share prices are going over the next few weeks and, hence, is playing John Maynard Keynes’s famous ‘beauty contest’ – seeking to anticipate how others will feel about these stocks in a few weeks’ time. The problem with this approach is that sentiment can be a fickle mistress and can change quickly and unpredictably.

“The most realistic distinction between the investor and speculator is found in their attitude toward stock-market movements. The speculator’s primary interest lies in anticipating and profiting from market fluctuations. The investor’s primary interest lies in acquiring and holding suitable securities at suitable prices.”

Source: Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor, 1949

Valuation, mispricing and where opportunity may lie

Periods of heightened economic uncertainty often lead investors to favour perceived stability and short-term predictability over longer-term value. When headlines are gloomy, many market participants gravitate towards companies whose earnings appear more resilient, even if that resilience is already fully reflected in valuations.

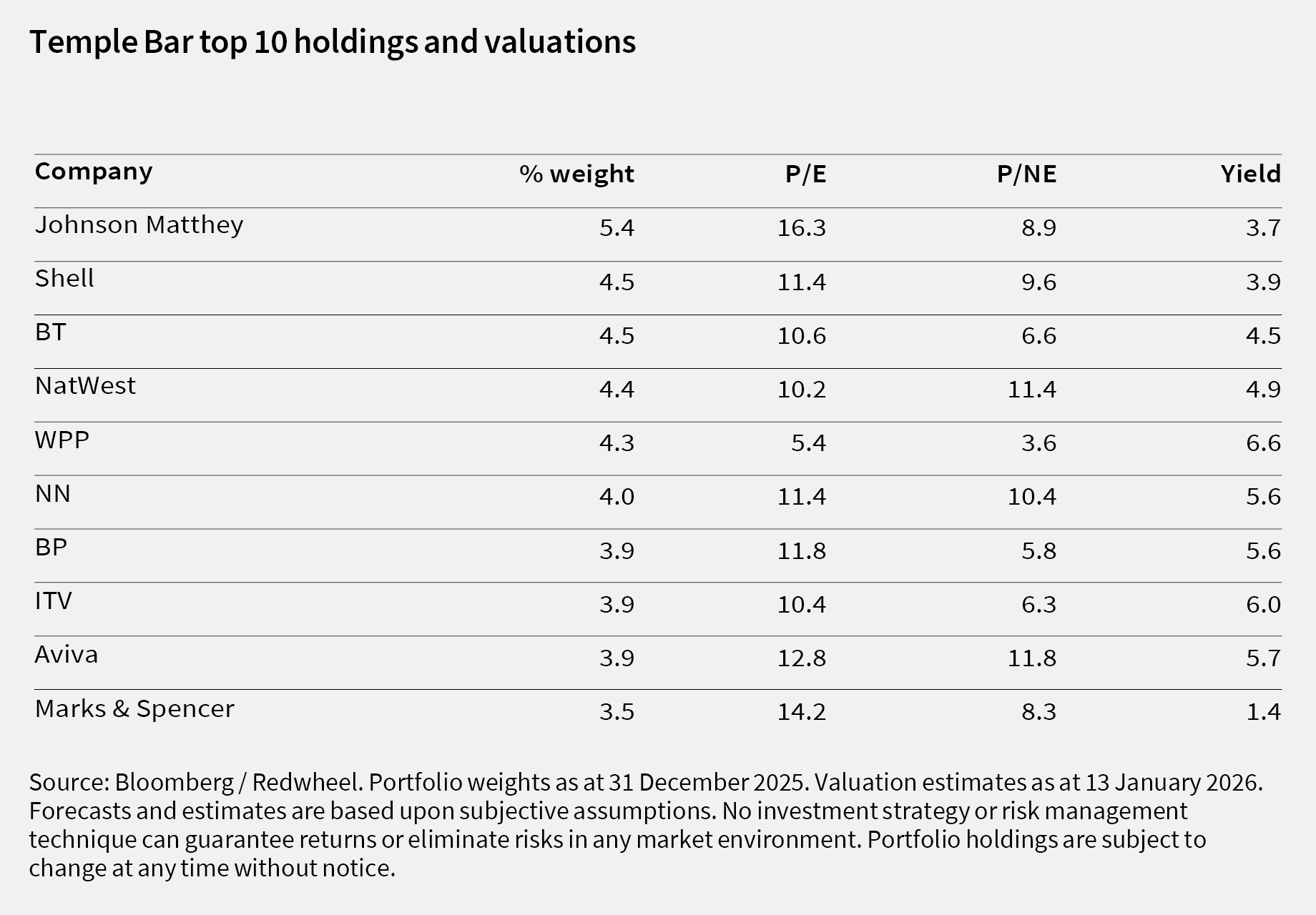

At the same time, businesses whose profits are more sensitive to the economic cycle are frequently marked down aggressively, regardless of their long-term prospects. This explains why several stocks in the portfolio, including media businesses WPP and ITV, are trading on 4-7% dividend yields and low price-to-earnings ratios (P/E). These valuations reflect the fact that most investors would currently rather sell these stocks than buy them.

We also include below a measure of price-to-normalised-earnings (P/NE), which reflects our assessment of a company’s underlying earnings power in a more typical year. This is important because, as explained earlier, near-term earnings can be depressed in a downturn, making conventional P/E ratios appear misleadingly high. Looking through this allows us to identify businesses whose long-term value – unaffected by the shorter-term earnings impact – is being under-appreciated by the market.

This valuation gap is not a coincidence. It reflects the behavioural tendencies described earlier – extrapolating short-term weakness, over-reacting to uncertainty and paying a premium for perceived stability. As Keynes observed nearly a century ago, it is precisely these fluctuations that create opportunities for patient, disciplined investors willing to look beyond the prevailing mood.

“It is largely the fluctuations which throw up the bargains and the uncertainty due to the fluctuations which prevents other people from taking advantage of them.”

Source: John Maynard Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936

Conclusion: discomfort, discipline and continued opportunity

Periods of heightened uncertainty tend to magnify short-term share price movements far more than they alter the long-term prospects of businesses. When investors allow media headlines and market sentiment to dominate their thinking, valuations can become disconnected from underlying fundamentals. We believe that for those willing to remain focused on long-term value, this divergence is not a threat – it’s an opportunity.

We understand that owning or buying cyclically-exposed businesses today may feel uncomfortable. Yet it has been our experience that it is precisely this discomfort that creates the conditions for long-term outperformance. As another very talented investor once said to me, “Some of my greatest investments made me feel physically sick at the time I put them on”.

In one of his regular investment memos, Howard Marks, co-founder and now co-chairman of Oaktree Capital, makes the same point:

“Most great investments begin in discomfort. The things most people feel good about – investments where the underlying premise is widely accepted, the recent performance has been positive, and the outlook is rosy – are unlikely to be available at bargain prices. Rather, bargains are usually found among things that are controversial, that people are pessimistic about, and that have been performing badly of late.”

Source: Oaktree Capital, April 2014

Despite the headlines, recent performance has been rewarding for Temple Bar shareholders, but this has not removed the opportunity set that our disciplined, valuation-led investment approach seeks to capture. Indeed, if anything, today’s pervasive economic pessimism may be helping to lay the foundations for the next leg of performance for patient UK investors to enjoy, as short-term anxiety once again creates long-term opportunity.

Thank you for your continued support.

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so.

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Nothing in this document should be construed as advice and is therefore not a recommendation to buy or sell shares. Information contained in this document should not be viewed as indicative of future results. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

This article is issued by RWC Asset Management LLP (Redwheel), in its capacity as the appointed portfolio manager to the Temple Bar Investment Trust Plc. Redwheel is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication.

Redwheel may act as investment manager or adviser, or otherwise provide services, to more than one product pursuing a similar investment strategy or focus to the product detailed in this document. Redwheel seeks to minimise any conflicts of interest, and endeavours to act at all times in accordance with its legal and regulatory obligations as well as its own policies and codes of conduct.

This document is directed only at professional, institutional, wholesale or qualified investors. The services provided by Redwheel are available only to such persons. It is not intended for distribution to and should not be relied on by any person who would qualify as a retail or individual investor in any jurisdiction or for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.

The information contained herein does not constitute: (i) a binding legal agreement; (ii) legal, regulatory, tax, accounting or other advice; (iii) an offer, recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell shares in any fund, security, commodity, financial instrument or derivative linked to, or otherwise included in a portfolio managed or advised by Redwheel; or (iv) an offer to enter into any other transaction whatsoever (each a Transaction). No representations and/or warranties are made that the information contained herein is either up to date and/or accurate and is not intended to be used or relied upon by any counterparty, investor or any other third party. Redwheel bears no responsibility for your investment research and/or investment decisions and you should consult your own lawyer, accountant, tax adviser or other professional adviser before entering into any Transaction.

How to Invest

The Company’s shares are traded openly on the London Stock Exchange and can be purchased through a stock broker or other financial intermediary.