In the last few years, some investors have ‘learnt’ that valuation no longer matters, as seemingly already expensive stocks have continued to soar to the skies, whilst lowly valued stocks have remained cheap. I continue to believe that this period has been the exception, not the rule (this time is not different) and will attempt to show why in this quarter’s letter to investors.

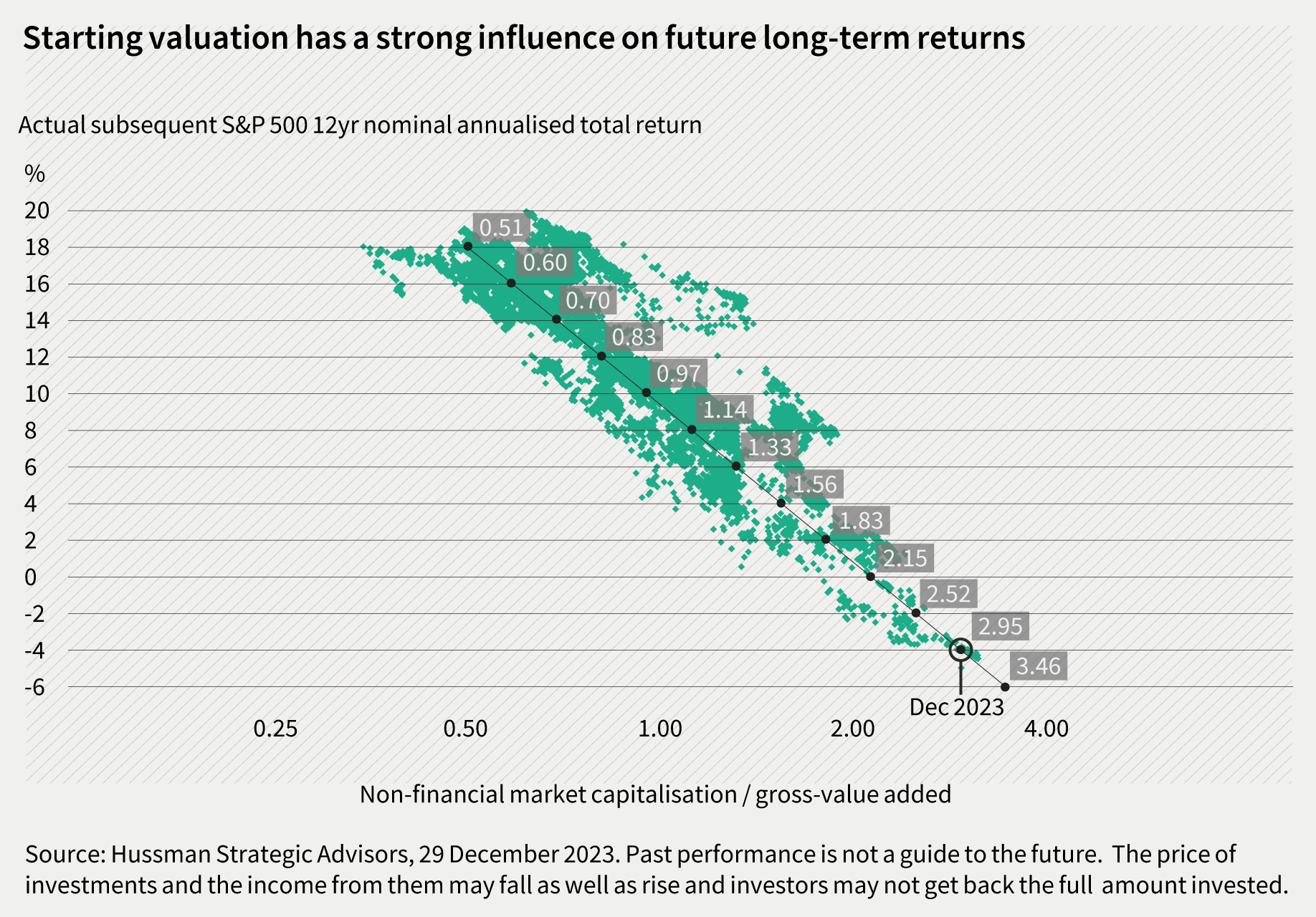

We start our defence with a chart showing the correlation of the valuation of the US equity market with the subsequent returns that were earned from it by investors. I believe this is one of the most important charts in finance.

Produced by US fund manager, John Hussman, the chart plots the valuation of the S&P 500 Index (across the x-axis) with the subsequent 12-year nominal annual return (on the y-axis). The lower valuations are on the left-hand side of the chart, and we can see how these closely match high annual returns. For instance, a valuation point of 0.60 tends to produce returns of about 16% per annum. Contrast this with the data on the right-hand side of the chart, where a valuation of 2.95 has historically resulted in annualised losses of 4% per annum over the subsequent twelve years.

Note two more things. Firstly, the author has highlighted the valuation that the S&P 500 at which closed 2023 and the fact that, historically, paying this valuation has led to long-term losses for investors. Secondly, note the lack of dots to the right of the end of 2023 valuation point. This is because the valuation of the US stock market at the end of 2023 was one of the highest ever observed in the period since 1928.

I find the (negative) correlation in the data above extraordinary. To put it in technical terms, the R-squared is -0.93 which implies a near perfect negative correlation between starting valuation and subsequent returns. In simple English, if you bought the US equity market when it was cheap, you received good returns in the following years, and when you bought it when it was expensive, you received bad (sometimes negative) returns. Furthermore, there have been virtually no instances in the period studied when that was not the case. Let’s now try to explain this link between valuation and subsequent returns.

The logic behind the relationship

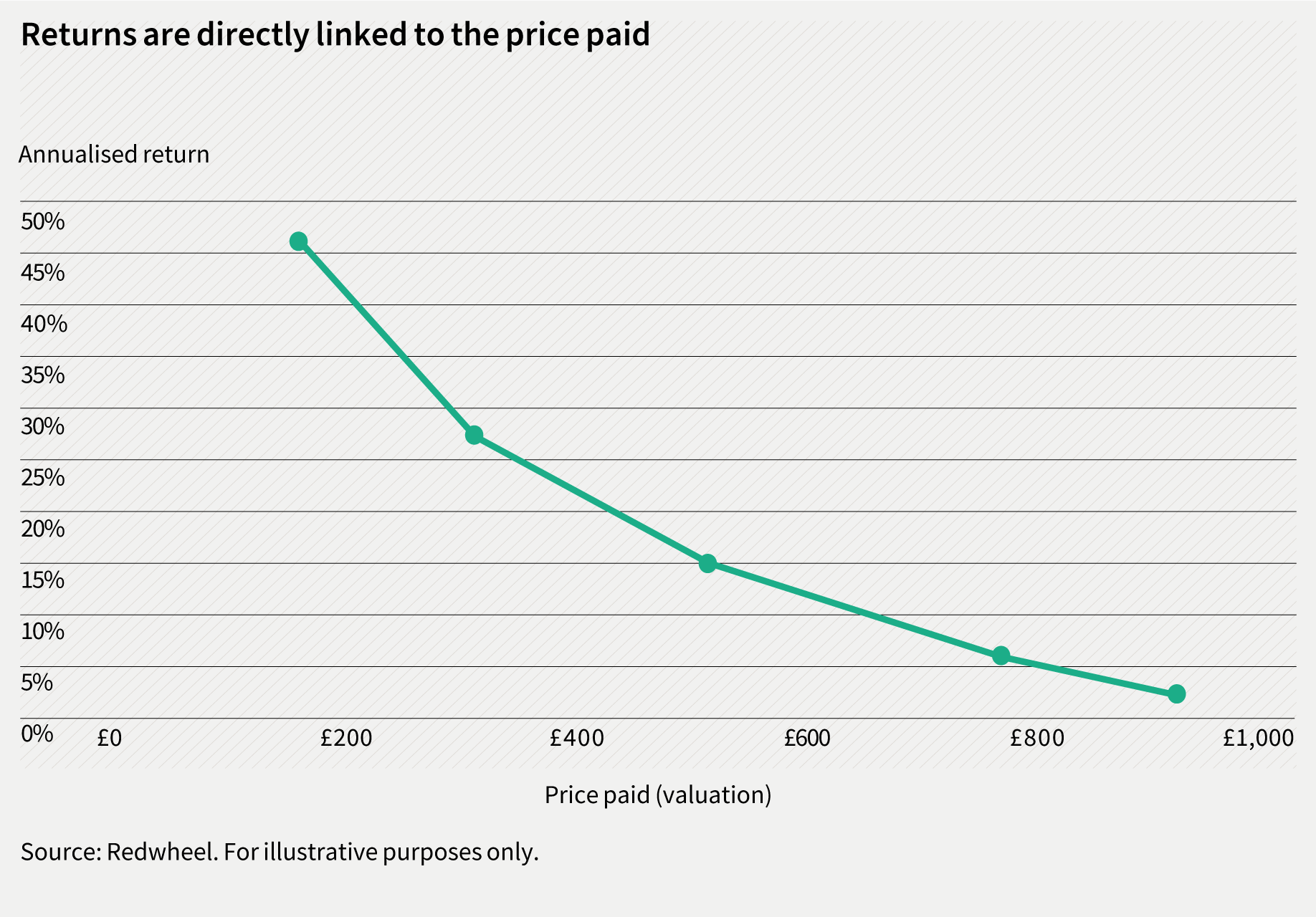

It helps to remind ourselves that when we invest in equities, we are simply buying a stream of cashflows, and the higher the price (or valuation) we pay for that stream of cashflows, the lower the rate of return we should generally expect to receive. To illustrate this point, let’s assume we are receiving £1,000 in five years’ time and then look at the annualised return we receive at various different purchase prices (see chart below). If we buy an asset for £150 today and it gives us £1,000 in five years’ time our annualised return is 46%, whereas if we pay £900 our return falls to 2% per annum.

Clearly, this is a theoretical exercise because, when investing, we don’t know precisely what the future return will be. It is, however, a useful exercise in demonstrating the logic that sits behind the enduring relationship between starting valuation and future long-term returns.

Nevertheless, armed with this knowledge, the obvious question to ask is why so many people, and this includes professional investors, would ignore it and do the opposite of what it implies? Evidently, many investors buy when valuations are high and subsequent returns are likely to be low and vice versa. In fact, more money went into the US stock market in 2021 at its all-time high than in the previous 20 years added together[1].

The influence of emotion

When people are buying groceries, a car or a house, they tend to act rationally and are able to make a sober assessment of the price relative to the value of the object they are purchasing. Unfortunately, when it comes to buying stocks, we tend to become emotional, and our decisions are often influenced by ‘fear’ and ‘greed’. When investors see stocks going up and other people getting rich (at least on paper), they have an overwhelming urge to join the herd and rush into stocks often at completely the wrong time. This is what produces stock market bubbles. Conversely, when we see bad news on the front pages and share prices are plummeting, investors often become fearful and sell at the wrong time.

We, as value investors, try to exploit this emotional behaviour in other investors by purchasing stocks where temporary bad news has pushed the share price well below the true value of a business. This is what famed US value investor, Warren Buffett meant when he advised investors to “Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

To illustrate this point, imagine that your friend has offered to sell you her ice cream van. You turn up to discuss the price with her on a wet Wednesday in March when she has sold three ice creams in six hours. The chances are she is likely to offer you a significantly better (lower) price for the business than if you met at the end of hot day by the beach in August when she has totally sold out by the middle of the afternoon. But let’s say that you intend to own this van for the next ten years. Then your assessment of its value can be based on the likely cash flows the business will produce over the whole period, bearing in mind all the seasonal ebbs and flows. Neither the slump in sales in March nor the buoyant sales of August have any real impact on the long-term value of the business and yet they are likely to have an emotional impact on your friend’s ability to price the business. If you are a value investor, you will buy the business during the March downpour rather than the summer heatwave.

This time is not different

Many of the most famous investors of the last fifty years have made their fortunes by following a value investing strategy with names such as Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger and John Templeton being synonymous with this approach. But despite this, value investing has fallen out of favour in recent years largely because the prolonged period of 0% interest rates and quantitative easing produced a bubble in the most speculative corners of the stock market where value investors were unlikely to be invested. As the price of things like Tesla and Bitcoin soared to previously unimaginable highs, funds invested in reliable but cheap businesses lagged the returns of the wider stock market. As a result, money began to flow out of value funds and into either ‘passive funds’ that tracked the wider stock market index, or growth funds which invested in high-flying technology stocks.

It is worth pointing out that this is not the first time this has happened. In the late 1990s, many investors abandoned value investing to chase the so-called dot-com stocks. This ultimately ended in disaster when the dot-com bubble burst and the next few years saw returns from the ‘old economy’ stocks handsomely outstripping those from the technology and telecoms sectors. Both the data above and the more than sixty years combined investing experience that Nick and I have, convince us that the negative correlation between valuation and subsequent returns is one of the immutable laws of investing. It is therefore one that we continue to adhere to in the way that we invest the money of the Temple Bar Investment Trust.

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so.

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Nothing in this document should be construed as advice and is therefore not a recommendation to buy or sell shares. Information contained in this document should not be viewed as indicative of future results. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

This article is issued by RWC Asset Management LLP (Redwheel), in its capacity as the appointed portfolio manager to the Temple Bar Investment Trust Plc. Redwheel, is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

Redwheel may act as investment manager or adviser, or otherwise provide services, to more than one product pursuing a similar investment strategy or focus to the product detailed in this document. Redwheel seeks to minimise any conflicts of interest, and endeavours to act at all times in accordance with its legal and regulatory obligations as well as its own policies and codes of conduct.

This document is directed only at professional, institutional, wholesale or qualified investors. The services provided by Redwheel are available only to such persons. It is not intended for distribution to and should not be relied on by any person who would qualify as a retail or individual investor in any jurisdiction or for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.

The information contained herein does not constitute: (i) a binding legal agreement; (ii) legal, regulatory, tax, accounting or other advice; (iii) an offer, recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell shares in any fund, security, commodity, financial instrument or derivative linked to, or otherwise included in a portfolio managed or advised by Redwheel; or (iv) an offer to enter into any other transaction whatsoever (each a Transaction). No representations and/or warranties are made that the information contained herein is either up to date and/or accurate and is not intended to be used or relied upon by any counterparty, investor or any other third party. Redwheel bears no responsibility for your investment research and/or investment decisions and you should consult your own lawyer, accountant, tax adviser or other professional adviser before entering into any Transaction.

How to Invest

The Company’s shares are traded openly on the London Stock Exchange and can be purchased through a stock broker or other financial intermediary.